By Arihant Paigwar

The increasing volatility and intensity of weather events, such as the October storms over the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea, have a very powerful message for India: climate risk has turned into economic risk without any doubt. Such events as Cyclone Montha, which hit near Kakinada with winds of about 110 km/h, tell us that the weather is changing drastically and that our everyday life is getting more and more fragile. This kind of instability is a part of a worldwide trend, which is well exemplified by the very catastrophic events like a Category 5 Hurricane Melissa that was estimated to cause losses of $6.5 billion in the Atlantic. It acts as a warning not only for the financial effects of global warming but also for the consequences of human activities that are still going on without any control.

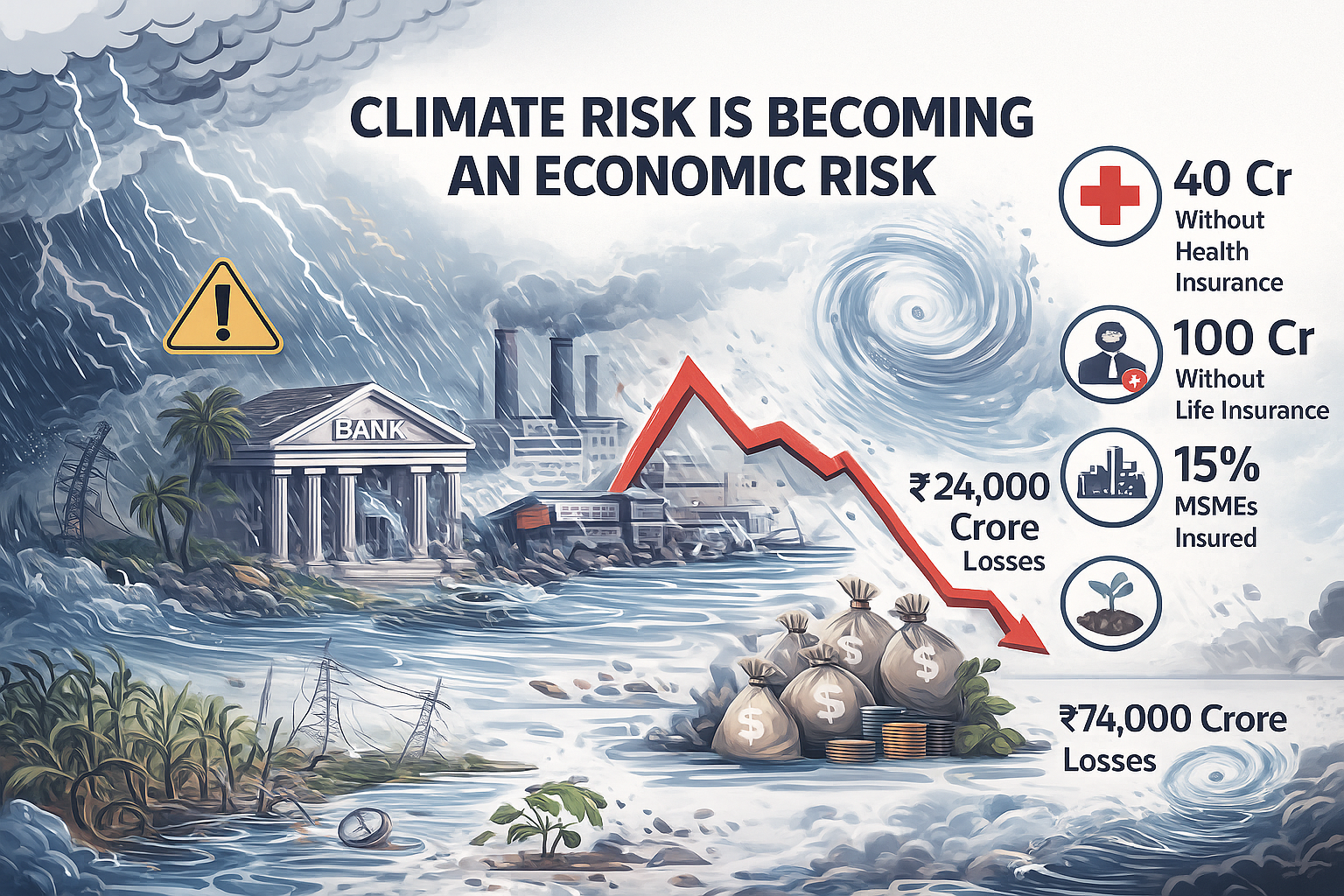

The consequences of climate volatility in India are manifold. It affects human lives, infrastructure, and even the money system. Just this year, during the monsoon season from June to September, irregular rains, floods, and landslides have killed more than 1,500 people, and the losses have been estimated to exceed ₹24,000 crore. The extreme rainfall that has been 27% higher than the Long-Period Average by mid-October has led to the destruction of the essential infrastructures like roads, bridges, schools, hospitals, and power lines in different states. The country is also exposed to major disruptions in various sectors, including agriculture, manufacturing, mining, and tourism. Therefore, the monsoon’s behaviour has transitioned from being a natural phenomenon to an important economic variable that has the power to change growth, employment, and fiscal stability.

As losses are rising to a great extent, the first and foremost question that a policymaker should ask himself/herself would be: where is the most significant protection gap? Although insurance is a very good tool for dealing with uncertainties, the majority of India’s people and economic activities have not been insured or have been only partly insured, which means that the losses are most of the time borne by individuals and enterprises who do not have any safety net. The figures disclose the extent of this exposure to risk: almost 40 crore citizens do not have health insurance, about 100 crore citizens are without life insurance, less than 15% of MSMEs have sufficient insurance, and roughly 70% of the gross cropped area is without any protection. In order to close this gap, India is taking the first steps towards climate-linked and parametric insurance models. These instruments are intended to facilitate automatic compensation when the weather conditions set in advance, for example, the intensity of rainfall or the speed of wind, are violated. These mechanisms aim to make the process of coverage faster, data-driven, and less difficult for the most vulnerable sectors, thus constituting a necessary advancement in the transition toward climate risk financing that has the capacity to absorb shocks at scale.

As climate volatility is becoming a matter of everyday life, India has to change its disaster response strategy from a focus on reactive relief efforts–what happens after the damage—to preventive planning and risk-building. The development of a country should not be judged only by indicators like GDP or production output, but also by the level of a society’s resilience–the ability to withstand shocks without losing its flow of life. Natural disasters, in the end, bring to light not only human weakness but also the power to adjust. Every storm that has been overcome is a kind of exam of how the protective systems, the responsive communities, and the collective will to rebuild stronger are at work. Hence, real growth is more about foresight than recovery rates.